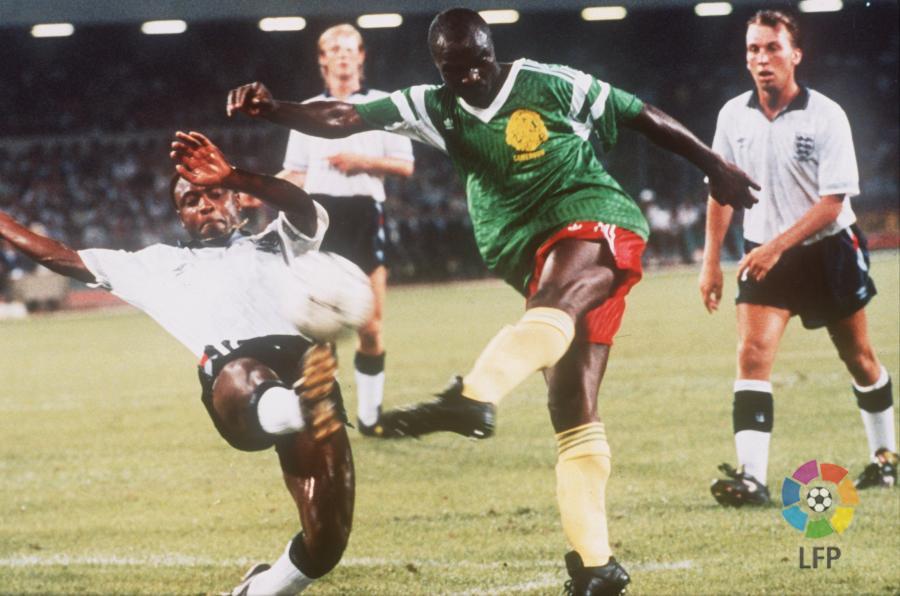

Samuel Eto’o will forever have the respect of the continent for being one of the most remarkable footballers Africa has ever produced. He is also to be commended for how he has expressed his commitment to the development of football in his home country Cameroon, both administratively (he is now President of the Cameroon Football Federation) and financially, using his own resources to bankroll expenses that should indubitably be made by the local Football Association. His words carry weight. It was therefore interesting for him to have made some comments about some of the Cameroonian players after the disappointment of their first-round defeat that seemed at the time to be signaling their exit from the tournament (they eventually rallied to qualify for the knock-out stages).

Eto’o had reportedly said:

“Dear brothers, I understand you. Many of you were not born in Cameroon and have never played for a club in Cameroon. The advice of a Cameroonian coach is beneficial to a footballer from the start of his career until the end. You who were born there have too many rights over the leaders. Cameroon taught me that I am a soldier within the National team. I will die with this spirit. Cameroon has just gone through humiliation just because love for the Fatherland is not 100% there…We made a mistake bringing you in to play for the flag. But after the AFCON, things will change. We are going to do a patriotism test before having young Cameroonians play in the National team…”

Like several African countries, Cameroon has in the recent past tapped into a reservoir of the country’s Diaspora to entice players who are second- and third-generation born abroad, to play for the country. There is a clear logic to this, as so many of these players have been schooled in the academies of previous colonial powers hence are of high technical, nutritional and conditioning standards to enhance their home-based contingent.

What is particularly interesting about Eto’o’s comments is how he is scapegoating these players, attributing them with ‘not getting Cameroon’ and therefore not as committed to the cause as those who were home-born would be. We can probably make allowances for Eto’o that he had allowed the raw emotions of his disappointment to occlude his logic. However, a brief perusal of social media quoting or reposting his message reveals that this is indeed a view shared by many across Africa.

Then there’s the sheer absurdity of what may constitute a ‘patriotism test’ – what would that even ask, or if asked, prove? I am imagining in Nigeria, they would ask you to sing the national anthem, or recite the pledge? That’s a memory test, not proof of patriotism. How many bowls of pounded yam can you consume? I have friends from other countries who can down bowls of the food. How many Afrobeats songs you can sing? Then half of the world nowadays would pass the test. Ask if they would be willing to go to war for the country? Given the current economic circumstances, most of the young people in the country seeking and using ever-more desperate attempts to escape to Europe would probably reply “Hell, No!” to that one, distinctively narrowing the pool of patriots Eto’o would have to choose from.

Yet, this Eto’o misspeak is but further evidence of what has been a long-standing trope and misunderstanding of the Diasporic Dilemma. Second and third-generation born children of postcolonial subjects tend to find themselves in a weird ‘in-between’ identity space, where they have had the rooting of their parents’ culture infused into them from birth, and the stemming of shaping and forging identities of belonging in the environmental spaces they traverse outside of their parents’ front door. This results in a sense of uneasy acceptance of the multiplicity of their identities and a freedom to traverse these as suits.

In recent times, the pervasive soft-power influence of popular culture has seen the ingraining of a strong sense of Africaness in Diaspora communities, which is manifesting itself in more children than ever strongly identifying with the culture and ethnic nationalities of their parents’ while retaining the civic nationalities of their countries of birth. Hence Bukayo Saka can easily play for England one day and ruck up in Lagos in an agbada the next, or Anthony Joshua can fly the British flag in the ring one weekend and happily be pictured prostrating before the governor of his mother’s home state in Nigeria the following one.

In the ongoing AFCON, the lie of Eto’o’s statement is easily revealed when you cursorily study the composition of several of the teams. The Defending Champions Senegal have almost half of their team born outside of Senegal. DRC, Cape Verde and Equatorial Guinea about 75%. Nigeria’s team consists of a rock-solid defence of Ola Aina, William Troost-Ekong and Calvin Bassey – and with Ademola Lookman, another Diasporan, they have been the team’s best players, performing with a conviction, pride and passion that fans of their Premier League teams are probably struggling to comprehend.

The most remarkable Diaspora story of AFCON so far though is that of young Malian striker, Nene Dorgele. Nene scored a magnificent goal in the Quarter-final match against Cote D’Ivoire, but rather strangely refised to celebrate the goal. Reason? – The 21-year-old was born in Kayes, Mali to Ivorian parents and spends most of his time during vacation in Abidjan. This is an unusual Diaspora case, as we are more used to discussing this as if it is something that only happens with people who have migrated to Western countries. One can only imagine how mind-blown Eto’o would be if this had been a Cameroonian player.

A recent report by Africa No Filter ‘Being African: How Young Africans Experience the Diaspora’ bear this out, finding that “diasporic African youths have a unique double heritage that makes them proud of African languages, food, music and history, while also strongly relating to the language and culture of their host country”. What this and few other reports have done though is fully consider the perceptions and attitudes towards Diasporans by their peers on the continent and the impact that this has on them. While absurd statements like Eto’o’s fuels this sense of opportunism, not really belonging and insufficient patriotism attributed to them, it is only hoped that a better balance will be seen when looking at all the other countries that have demonstrated how strategically mobilising and embracing the Diaspora has resulted in them being better teams.

We should all do this – the Diaspora is set to become an even more massive contributor to Africa’s future beyond remittances than ever before. Football is just an indicator of this. We all want the continent to be successful and the Diaspora is a key ingredient of that success.

And I still love Eto’o. :-)

©Olu Alake 2024.

Readers of Lola Shoneyin’s brilliant 2010 novel about gender politics, sexual dynamics and the uneasy traversing of the contemporary – traditional social continuum in modern Nigerian (specifically Yoruba) marriages, might have received the news of a stage adaptation with some apprehension: would a simple story with such complex underlying narratives and colourful characters translate readily to the stage? Having seen the job that has been done under Femi Elufowoju Jr’s masterful direction in Arcola’s main space, all such fears were very quickly abated. This is one vibrantly enjoyable evening of theatre that adds vivid colour to London’s stage scene.

Readers of Lola Shoneyin’s brilliant 2010 novel about gender politics, sexual dynamics and the uneasy traversing of the contemporary – traditional social continuum in modern Nigerian (specifically Yoruba) marriages, might have received the news of a stage adaptation with some apprehension: would a simple story with such complex underlying narratives and colourful characters translate readily to the stage? Having seen the job that has been done under Femi Elufowoju Jr’s masterful direction in Arcola’s main space, all such fears were very quickly abated. This is one vibrantly enjoyable evening of theatre that adds vivid colour to London’s stage scene. photo credit: idil sukan

photo credit: idil sukan

When Cont Mhlanga wrote Workshop Negative soon after Zimbabwe’s independence in 1980, he obviously didn’t expect it to have a life beyond making an immediate impact in his native land. After touring Zimbabwe in 1986, Workshop Negative was banned by the government (for ‘discrediting the office of the president’, no less), Mhlanga was imprisoned and narrowly escaped having his writing fingers amputated as punishment. His travails nevertheless precipitated the development of Zimbabwe’s post-independence township theatre form which has engendered other masterful pieces and fostered the nurturing of a generation of actors and musicians.

When Cont Mhlanga wrote Workshop Negative soon after Zimbabwe’s independence in 1980, he obviously didn’t expect it to have a life beyond making an immediate impact in his native land. After touring Zimbabwe in 1986, Workshop Negative was banned by the government (for ‘discrediting the office of the president’, no less), Mhlanga was imprisoned and narrowly escaped having his writing fingers amputated as punishment. His travails nevertheless precipitated the development of Zimbabwe’s post-independence township theatre form which has engendered other masterful pieces and fostered the nurturing of a generation of actors and musicians.

The performances of Jude Akuwudike, Danilo Antonelli and John Pfumojena are inspiring: the form of the play is intensely physically demanding, and the piece relentlessly crackles along to its fraught conclusion. Interspersing the hour-long (no interval and you won’t notice) break-neck narrative is some epic singing – ‘Tshotsholoza’ is particularly spine-tingling. The intimate space of the Gate Theatre is maximised by the clever design of Colin Falconer to convey an almost claustrophobic sense that the protagonists will relentlessly and inevitably rub each other up the wrong way.

The performances of Jude Akuwudike, Danilo Antonelli and John Pfumojena are inspiring: the form of the play is intensely physically demanding, and the piece relentlessly crackles along to its fraught conclusion. Interspersing the hour-long (no interval and you won’t notice) break-neck narrative is some epic singing – ‘Tshotsholoza’ is particularly spine-tingling. The intimate space of the Gate Theatre is maximised by the clever design of Colin Falconer to convey an almost claustrophobic sense that the protagonists will relentlessly and inevitably rub each other up the wrong way.

As we saw in US with the reaction of many to the #BlackLivesMatter campaign which some spectacularly misjudged and deemed so divisive it elicited the #AllLivesMatter response, it seems that there is a Western media defined kinship recognition comfort level which legitimises the empathy for and inclusion of suffering peoples. If they are ‘like us’ or are affected in one of ‘our places’, then their suffering is worthy of a widely shared hashtag. If they are frankly, killing each other, (Kurds killing Turks? Africans killing Africans? Nothing to see here, it seems)… maybe we just report it for a day on the news channels and then swiftly move on.

As we saw in US with the reaction of many to the #BlackLivesMatter campaign which some spectacularly misjudged and deemed so divisive it elicited the #AllLivesMatter response, it seems that there is a Western media defined kinship recognition comfort level which legitimises the empathy for and inclusion of suffering peoples. If they are ‘like us’ or are affected in one of ‘our places’, then their suffering is worthy of a widely shared hashtag. If they are frankly, killing each other, (Kurds killing Turks? Africans killing Africans? Nothing to see here, it seems)… maybe we just report it for a day on the news channels and then swiftly move on.